| The Public Utility Company Act of 1935

INTRODUCTION

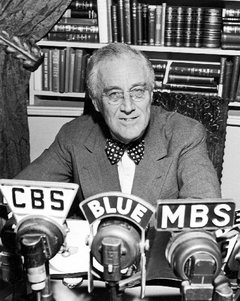

More than halfway into his first term of office, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's New Deal switched directions. While its initial emphasis was on immediate recovery from the economic devastation of the Great Depression, 1935 saw a shift towards fundamental reforms of the American economy. One of the centerpieces of the "Second New Deal" was the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, also known as the Wheeler-Rayburn Act. Aimed at regulating an industry that had been allowed to operate virtually unchecked, the Act prompted one of the hardest fought congressional battles in American political history. The public utility lobby, whose members had used the holding company device to increase their power and wealth at the expense of the ordinary consumer, waged an all out campaign to squash this bill. They might well have succeeded if not for the tenacity and skillful political maneuvering of three men — Congressman Sam Rayburn (D-Texas), Senator Burton K. Wheeler (D-Montana) and Senator Hugo Black (D-Alabama). As a result of their efforts, Roosevelt was eventually able to sign an act which successfully regulated the power industry for almost seventy years.

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

A holding company can be generally defined as any corporation formed for the express purpose of controlling other corporations through the ownership of a majority of its voting stock. The corporation which is to be controlled by the holding company is commonly referred to as a subsidiary. [1] There are basically two forms of holding companies. The first is one which derives its profits solely from the investments in the securities of its subsidiaries. These are called "investment holding companies." [2] The second type, which may or may not derive profits from investment securities, also receives profits from transactions with the subsidiaries and is called a "management holding company." [3]It is this second form of holding company which dominated the public utility industry and created the abuses targeted by the Wheeler-Rayburn Act. [4]

The American electric power industry was essentially born on September 4, 1882, when Thomas Alva Edison switched on his Pearl Street generating station's electrical power distribution system, and provided 110 volts of direct current to fifty-nine customers in lower Manhattan. [5]Soon thereafter, holding companies began to appear. [6] The early holding companies were not evil per se. In fact, they provided certain advantages. During the early years of the industry, if an individual bought several companies, he would often use this device as a legal instrument to direct them. Most of the early holding companies were nothing more than a vehicle used to manage operations located in several localities, and usually spread across more than one state. [7]The holding company's primary benefit was that it helped utilities to reduce construction and operation costs by taking advantage of naturally occurring economies of scale. [8]It also allowed the interchange of equipment and facilities among different operating companies. [9] Other benefits included the ability to obtain more favorable financing, the ability to mobilize more experienced labor among various operating companies, greater efficiency in the use of fuel, and centralized management. [10]

|

|

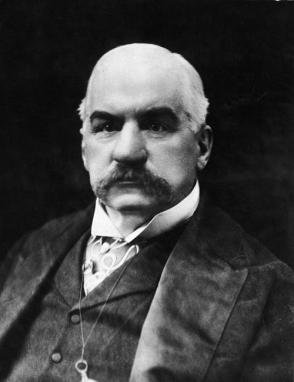

J.P Morgan |

During the Coolidge administration, holding companies underwent a shift in character. Instead of a means to provide better, more efficient service, they were now predominantly used to engage in stock speculation and perpetrate other assorted financial abuses. [11]The types of abuse which Roosevelt targeted with the Public Utility Holding Company Act were best typified by two men - Samuel Insull and J.P. Morgan. Even though he died in 1913, more than two decades before the Act became a reality, Morgan is credited for creating the predatory climate that necessitated its passage. [12]He targeted the utility industry almost from its inception by using his financial leverage to force his way into a partnership with Edison. [13] By 1892, Morgan had pushed Edison out of Edison General Electric Co., and merged it with the Thomson-Houston Electrical Co. This newly merged company became the General Electric Corporation. By the 1920's, the Morgan Bank also controlled the United Corporation, giving the House of Morgan command over two of the industry's giants. [14] However, it was Insull who would come to be viewed as the poster boy for holding company abuse.

A native of England, Insull began his career by working as a clerk for various

|

|

Samuel Insull | businesses in London. He soon met Edison, who brought him to the United States in 1881 to serve as his personal secretary. Insull managed the inventor's businesses and was indispensible in helping Edison open New York City's Pearl Street station. In1892, Insull left New York and moved to Chicago to lead the Edison firm located there. [15] As an operating chief, Insull knew no peer. He acquired a network of gas, light, power and transit companies spread over 32 States from North Dakota to Florida to Maine. These companies served some ten million people, had securities with a market value of over $3 billion, and had a combined earning power of over $500 million a year. [16]

These men and the companies they operated were in a unique position of power. This was not just another commodity they controlled. This was the supply of vital electrical energy, the very thing which heated and electrified homes, drove the agricultural process, and powered factories. This was a part of the nation's infrastructure, indispensable to both its advancement and continued survival. [17] Given their control over such a crucial resource, it would have been idyllic had these men embraced their role as de facto fiduciaries for the public good. Unfortunately, as is often the case, greed and the lust for power won out over the noble idea.

Holding companies were built through a process known as "pyramiding." At the bottom of the pyramid would be the operating utilities which were actually generating and distributing electricity. Control of the operating company was gained by an unrelated corporate entity by purchasing a controlling interest of its voting stock. These holding companies were, in turn, bought by other holding companies until many "levels" were added to the pyramid's structure. [18] Pyramiding was attractive to investors for two reasons. First, it reduced the amount of funds that were needed to gain control of operating utilities. In fact, the farther removed a holding company was from the operating subsidiary at the base of the pyramid, the less capital it took to control it. Second, it dramatically increased the amount of income which would flow to the holding company at the apex of the pyramid. [19] For example, assume an operating company was worth $100 million, and was capitalized 50 percent by bonds, 25 per cent by preferred non-voting shares (which earn a fixed return), and 25 per cent by common or voting stock. Control of the entire $100 million in assets could therefore be bought by purchasing all the voting stock for $25 million. The company making this purchase would be referred to as the "first tier company". If the first tier holding company is capitalized in the same manner as the operating companies (50 per cent debt, 25 per cent preferred shares, 25 per cent voting shares), then control of this company could be acquired by a second level holding company for $6.25 million, an amount sufficient to purchase all of the voting shares. That second level holding company could then be purchased by a third level holding company for $1.56 million. The fourth level holding company could purchase control in the third level holding company for less than $391,000. This small expenditure by the fourth level holding company would then be sufficient to control the $100 million worth of operating utility assets.

Further, if the value of the assets of the operating company went up by 10 per cent ($10 million), all of the increase accrued to the share holders of the voting stock of the highest level holding company, resulting in an increase in the value of the fourth level holding company shares equal to more than 25 times the original investment.

Pyramiding of this magnitude became the rule rather than the exception. The Securities and Exchange Commission noted that usually five to six tiers of holding companies were placed on top of the operating companies. In some cases, the figure was as high as twelve. [20]

In a 1928 report to the 70th Congress, the Federal Trade Commission found that one five tier holding company produced a return of 295 per cent to the top holding company on returns which averaged only 5 percent for the operating companies. The report went on to conclude, "The highly pyramided holding company group represents the holding company system at its worst. It is bad in that it allows one or two individuals, or a small coterie of capitalists, to control arbitrarily enormous amounts of investments supplied by many people." [21] Since the holding companies at the top of these pyramids were so far removed from the actual consumers of electricity, customer service and reliability naturally suffered. In addition, consumers often paid obscenely high rates because they were, in effect, subsidizing speculative ventures. This, in turn, further benefited the holding companies - the higher the rates, the greater the increase in the speculative value of the holding company's stock. [22]

This practice of pyramiding opened the door to still further abuses by the holding companies. Among these was the "write-up" of its assets and stock. This term refers to the process of increasing the accounting value of an asset on the company books. This was very easy to do, particularly in an age where securities regulation was still in its infancy. The FTC investigated 18 of the largest holding companies, their 42 sub-holding companies, and the 91 operating companies which they controlled. The investigation found combined assets amounting to $8.5 billion. The investigation concluded that these assets were overvalued by at least $1.5 billion. The FTC report indicated three ways by which these write ups were accomplished and the inflated values were achieved :

(1) Inflated construction costs;

(2) Inflated values of the shares of subsidiary holding companies and operating companies due to the internal sale of those shares at above market prices;

(3) Write-ups of values of the consolidated company based upon optimistic judgments of the economies that would be achieved by the consolidated company with a resulting overestimation of the potential earning power of the holding company.[23]

The lack of effective regulation also made it possible for holding companies to engage in a practice known as "self-dealing". In theory, the holding companies were supposed to provide additional stability to the operating companies, but by the early 1920's they were actually milking the operating companies in three ways:

(1) The operating utility would borrow money on its good credit and then lend all or part of the proceeds to the holding company, receiving only an unsecured note from the parent holding company in return.

(2) The holding company would lend money to the operating company at interest rates well above what the operating company could have obtained in the market from an independent, third party lender.

(3) The operating company would be forced to pay unjustifiably high dividends to the holding companies. [24]

The holding companies also abused the operating companies by levying excessive fees for the services the holding company rendered. The operating utility would receive engineering, construction, management, and financial services from the holding company's centralized staff or from another corporation within the holding company structure. While the general standard was that these fees should not exceed costs plus a fair margin of profit, the FTC found that most of these payments had been exorbitant when judged by this standard. Consumers were adversely affected because these fees were generally passed on to them in the form of higher rates. [25]

However, the investing public was either oblivious to these practices or chose to ignore them altogether, as evidenced by their desire to invest in these companies. During the 1920s, one-third of all corporate financing in America was issued by utility companies. However, once the speculative bubble burst, and the Insull Empire eventually fell, these abuses came to light. [26]

When the stock market crashed in 1929 millions of Americans who held common stock in the utility holding companies lost hundreds of millions of dollars. Between 1929 and 1935, American power production fell by almost one-third. The destruction of Insull's holding company during the early years of the Great Depression was the most spectacular, wiping out the life savings of 600,000 shareholders. These failures further decimated an already broken economy. [27]They also strengthened the Roosevelt administration's resolve to rid the American business scene of these parasitic devices once and for all.

ABOLITION OR REGULATION?

Fresh from legislative victories that had reformed both the securities market and the stock exchange, FDR set his sights on the public utility holding companies in late 1934. The president saw their destruction as the last piece of unfinished business in realizing his dream of economic justice for all Americans. To him, their very existence was an anathema. [28]

|

|

Franklin Delano Roosevelt |

There was certainly enough raw data to support Roosevelt's position. The Federal Trade Commission had been engaged in the afore-mentioned investigation of the industry since 1928. Additionally, the House Interstate Commerce Committee launched a similar inquiry in 1930.

Judge Robert E. Healy, who headed the FTC investigation, and W.M.W. Splawn, who spearheaded the House probe, dredged up volumes of intricate and tedious facts documenting these patterns of abuse. The National Power Policy Committee (NPPC) authored a report in early 1935 which effectively summarized the findings of these two inquiries.[29] According to the NPPC report, thirteen holding groups controlled three-quarters of the privately owned electric utility industry. The three largest groups — United Corporation, Electric Bond & Share (EBASCO) and the Insull Group controlled some forty percent by themselves. The report went on to state, "Such intensification of economic power ...not only is susceptible of grave abuse but is a form of private socialism inimical to the functioning of democratic institutions." [30]

The NPPC report concluded that the only remedy was "the practical elimination...of the holding company where it serves no demonstrably useful and necessary purpose."[31] Therefore, Roosevelt was faced with a fundamental decision — whether to introduce a bill that regulated the holding companies or destroyed them. Many felt the president made his feelings clear when he misdelivered one line of text in his State-of-the-Union address to Congress on January 4, 1935. The manuscript of the speech spoke of "the abolition of the evil features of holding companies." However, FDR read it as the "abolition of the evil of holding companies." While Roosevelt tried to explain away the mistake in a subsequent press conference, it soon became obvious that this may well have been a Freudian slip. [32]

|

|

Rep. Samuel T. Rayburn (D-Texas) |

Several days after his address, FDR convened an informal committee of various governmental officials at the White House to review a proposed bill drafted by senior advisors Ben Cohen and Tommy Corcoran. Among those attending were Rep. Samuel Rayburn (D-Texas), chairman of the House Committee on Foreign and Interstate Commerce, as well as both Splawn and Healy. [33] Cohen and Corcoran's initial draft stopped short of complete abolishment. They proposed that the holding companies be required to simplify their capital structure and limit their operations to a single integrated system. Their bill was initially worded to sound as moderate as possible. On the other hand, the rest of FDR's impromptu committee favored a law ridding the country of all utility holding companies that could not prove they served a useful purpose. While withholding public support of such measures, Roosevelt privately instructed his two advisors to craft a bill that would lead to the ultimate abolition of the holding companies. [34] Under the revised version of the bill, all holding companies would have to register with the Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) and follow its strict rules in regards to submitting financial reports. Additionally, the holding companies had to obtain SEC approval before issuing stocks and bonds.

However, as it turned out the major bone of contention would be what power executive, and future Republican presidential candidate, Wendell L. Wilkie labeled as the "death sentence" clause. This part of the bill stated that the utility companies should voluntarily get rid of those holding companies which had no useful function. But, should that not be carried through within five years, on January 1, 1940, the SEC would be empowered to compel the dissolution of every holding companywhich did not establish an economic reason for its existence. As a practical matter, most holding companies would be dismantled. [35]

|

|

Sen. Burton K. Wheeler

(D-Montana) |

Roosevelt tabbed Rayburn to sponsor the bill in the House. He then called in Burton K. Wheeler (D-Montana), chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, to introduce the legislation in the Senate. Initially, the administration's plan was to push the bill through the House first. Accordingly, on January 11, 1935, Rayburn set the tone in a speech before the full House. The legislator from Texas labeled the utility holding companies as the "master" of the American people and stated, "If left alone (they) will jeopardize our financial institutions and perhaps destroy the Republic." [36] Less than a month later, on February 6, 1935, both Rayburn and Wheeler introduced the administration's bill in their respective chambers. If passed, the law would abolish more than 91 percent of the existing utility holding companies. This set into motion what many historians have called, "the greatest congressional battle in history."

THE UTILITY INDUSTRY FIGHTS BACK

The punitive nature of the Wheeler-Rayburn Act caught the utility industry by surprise. They had been expecting a movement to regulate the holding companies, not abolish them. The industry's response was swift, powerful and predictable. [37] The bill's first stop was Rayburn's House Committee on Foreign and Interstate Commerce, which would hold hearings and consider evidence on the proposed legislation. The utility industry countered by immediately mobilizing a lobbying campaign that was unprecedented in its scope and intensity. The utilities' summoned individual investors, banks, savings and loan depositors, insurance policy holders and other industrialists to join them in the fray to "save free enterprise." According to one estimate, this created a base of 14 million individuals who could potentially stand against the Wheeler-Rayburn Act. [38] Additionally, utility lobbyists descended on the Capitol in droves. The industry soon had more than 600 lobbyists in Washington, outnumbering the 531 members of Congress. [39] The power barons quickly formed a group called "The Committee of Public Utility Executives" and headquartered it at Mayflower Hotel, where many of the congressmen and senators stayed while the legislature was in session. Representing most of the U. S. power business, this organization's stated purpose was to issue memoranda, offer analyses of the proposed legislation, prepare statements, and encourage protest among its shareholders. In reality, its function was to apply constant pressure on the lawmakers who would decide the fate of the bill. [40]

The utilities next order of business was to launch a propaganda campaign aimed at misleading millions of investors into believing their entire investment would be lost if the bill became law. Lists of stockholders were compiled by congressional district and tendered to each member of Congress to illustrate the Act's adverse effect on constituents. [41] The utilities also sought to sway public opinion through newspaper, magazine and radio advertising. While some of these ads stuck to factual data in an attempt to appeal to reason, many tried to play on the public's emotions. For example, United Gas Improvement Co., the oldest public utility holding company in the country, and one of the soundest, displayed a group of what appeared to be widows, orphans and pensioned bookkeepers under the caption: "Think it over, Uncle Sam!" [42] This was accompanied by a relentless campaign which flooded Congress with an avalanche of letters and telegrams. Missouri Senator Joel Bennett Clark declared that he received 6,000 protests in a single day. It was estimated that by the end of March, at least 500,000 citizens had urged their representatives to kill or modify the bill. [43]

In response to these efforts Roosevelt, who had not yet publically endorsed the Wheeler-Rayburn bill, finally made a pitch for its passage on March 12th. He pointed out the law was designed to protect the ordinary investor, not wipe them out. He then stated that, "except for where it is absolutely necessary to the continued functioning of a geographically integrated operating utility system, (the holding companies) must go." [44]

Several weeks later, speaking to a conference of banking officials, Thomas N. McCarter, president of the Edison Electric Institute, validated an ugly rumor that was already circulating around Washington. "The President has an obsession on this subject," McCarter said. "It is a condition of mind that even many of his closest associates in Washington do not understand." McCarter later repeated this same line before twelve hundred utility officials at the Institute's annual meeting, thereby further fueling questions about FDR's mental state. [45]

Against this back drop of unyielding pressure, the Rayburn committee sat through two months of exhaustive testimony. In all, 34 witnesses testified against the bill and eleven others urged its passage. The lead witness for the utilities was Wilkie, the president of the Commonwealth and Southern Corporation. His outstanding record as a utility executive and his powerful personality made him the perfect spokesman for an industry that was fighting for its life. Wilkie smartly conceded that there had been grave abuses in the utility industry. However, he argued that this was no reason to destroy the holding companies, which were necessary to provide financing for the operating companies. According to Wilkie, effective regulation would prevent these abuses from occurring in the future. [46]

At the conclusion of the testimony, a six member sub-committee headed by Rayburn was formed to scrutinize and redraft the original bill. When they reached section 11, the "death sentence" clause, it became apparent that there was a hopeless deadlock. The New Dealers soon realized they lacked the votes to save the death sentence provision. Rayburn, Wheeler, Corcoran and Cohen were forced to consider a new approach. Accordingly, it was agreed that Rayburn would slow down and allow the Senate, which was thought to be more agreeable to the death sentence section, to act first. The group reasoned that passage in the Senate might sway some of the more reluctant congressmen. [47]

THE SENATE DELIVERS

As Wheeler prepared to take the bill before the Senate, he was warned by an emissary from the utility lobby that if he persisted in fighting for the Act, his political career was all but finished. This threat had no effect on the fiercely independent lawmaker from Montana, who replied, "Tell them that to me a holding company is like Jesse James without a horse, and you can't scare me out of this fight." [48]

Realizing that passage of the bill in the Senate could hinge on as few as one or two votes, the utility lobby also tried these scare tactics on an unassuming freshman senator from Missouri.

"Representatives of the public utilities lobby came to see me and asked me to vote against the bill," the Harry S Truman recalled. "I told them I was personally opposed to the monopolistic practices which were squeezing the consumers to death and that I would vote in favor of the bill. Next the lobby sent people to Missouri to get the Democratic organization there to exert pressure on me. That failed also. And finally, a propaganda campaign financed by the utility magnates was launched in the state of Missouri among my constituents, many of whom held securities. I was swamped with letters and telegrams."

The neophyte senator still refused to bend. Truman burned over 30,000 messages which had piled up on his desk. The future President, who would be an outspoken critic of corporate greed throughout his political career, followed his conscience and continued to support the bill. [49] On June 11, 1935, the death sentence clause came up for a vote before the full Senate. Democrats loyal to FDR were joined by a group of progressive Republicans, and the clause narrowly passed by a 45-44 vote. The entire bill then quickly passed the Senate by a vote of 56-32. [50]

DARKNESS BEFORE THE DAWN

The fight then shifted back to the House. Within a week, the sub-committee voted to eliminate the mandatory death sentence provision. In its place was a much weaker version that would still allow the SEC to dissolve a holding company, provided it could prove that such action was in the public interest. However, by shifting the burden of proof to the Commission, the sub-committee effectively stripped the bill of any substantive power to abolish the holding companies. The bill was quickly approved by the full Commerce Committee and referred to the House Committee on Rules, where the terms and conditions for its debate before the full body would be determined. [51] After a secret poll showed that he lacked about forty votes to pass the death sentence, Rayburn then pressed the Committee on Rules to order a roll-call vote on the bill. He reasoned that he might have an outside shot at saving the clause if the members had to vote in public and answer to their constituents. However, once again Rayburn was rebuffed. The House members were allowed to cast their votes in private. [52]

|

|

Wendell Willkie |

With the matter coming before the full house, both sides increased their lobbying efforts. Roosevelt dispatched an army of lieutenants to canvas the House members. These men pled, threatened and bargained for a vote. Corcoran set up a temporary command post in an empty office next to the Rayburn committee hearing room. His job was to keep tabs on those who promised to support the bill and make sure no one vacillated. This mimicked some of the utility lobby's tactics was seen as a sign of desperation on the part of the Roosevelt Administration. [53] Confident of a victory in the House, the utilities continued to hammer the legislators. Privately, local power executives informed the lawmakers of the industry's intention to defeat anyone who voted for the death sentence. Utility officials also openly boasted that theirs was the most powerful lobby ever assembled. Further, McCarter's previous remarks about Roosevelt's "obsession" and "condition of mind" were still having an effect. By mid-July, Time reported that its Washington correspondents were being plagued with inquiries asking whether the President was on the verge of mental collapse. As evidence of his mental decline, the rumors pointed to a fit of laughter he had during a press conference and an alleged "violent fit of hysteria" that occurred after hearing the Supreme Court's NRA verdict. [54]

In addition to these unscrupulous methods, the utilities relied even more on the people back home to exert pressure on their congressman. To that end, more than 800,000 letters and telegrams flooded the halls of Congress during the last two weeks of June. However, the validity of these letters soon came into question. On June 27th, Rep. Denis Driscoll (D-Penn.) received 816 telegrams from Warren, a borough in his district. As he scanned these documents, two things caught his attention. First, all the telegrams were from people whose surnames began with the first four letters of the alphabet. Second, although he knew Warren fairly well, he did not recognize most of the correspondents. Where he did recognize a name, Driscoll sent a letter explaining why he was supporting the Wheeler-Rayburn bill. Within a few days, his constituents informed him that they had not sent any such telegrams. He was also receiving bundles of telegrams from Meadville, another town in his district. He decided to send wires to a few of the Meadville names. Western Union informed him these addresses did not exist.[55] Both the forged letters and the "whisper campaign" would come back to haunt the utility lobby. However, at the time Driscoll made his discovery, the House was already debating the bill. The bill's prospects of enactment were starting to look bleak.

Rayburn opened the debate with another impassioned plea for the death sentence provision. Rep. George Huddleston (D-Alabama) then stood and stated the case opposing this section. Huddleston began by chastising both sides;

"I deplore these outside influences. Before we had the first hearing on this bill the chairman of our committee [Rayburn] radioed from one end of the country to the other telling the people how bad the utilities were and how much this kind of legislation was needed. He was not alone in riding this wave. . . . The Chief Executive through his all-powerful influence had repeatedly done so. Let us have done with this talk of propaganda. Both sides are guilty. Both have interfered with a fair and just decision upon the part of Congress."

Huddleston went on to chide Rayburn for not backing his own committee's bill. He then read the 1932 Democratic Party platform which called for regulation rather than abolition. "Upon that plank, I will stand," he asserted. By the time Huddleston was finished, he received one of most enthusiastic ovations in the history of the House. Rayburn instinctively knew what this meant. Although there would be many more hours of debate, the House was decidedly opposed to the death sentence provision. [56] After a staggering twenty-two and a half hours of debate, the matter was finally put to a vote on July 1, 1935. The death sentence amendment was rejected by a vote of 216-146. The House then passed a diluted version of the bill the next day, 323-81. According to the New York Times, this was, "the most decided legislative defeat to President Roosevelt since he assumed office." [57]

The next round would be fought in a joint House-Senate conference committee which Wheeler would chair. Given the drastic differences in the House and Senate versions of the bill, it appeared a deadlock was likely. Many believed the two sides would be unable to reach a compromise, and the Wheeler-Rayburn bill would die in the committee. As the St. Louis Post Dispatch stated, "The power industry was too strong for Congress." [58] However, all was not lost. While the power industry may have been too strong for Congress, it was not strong enough to overcome the investigative skills of Hugo Lafayette Black.

THE BLACK INVESTIGATION

The top news story of July 2, 1935, was the House's passage of a holding company bill that eliminated the death sentence clause. Lost in the hoopla was an event that would have a much longer lasting and important impact on the nation — Alabama's Hugo Black was appointed to head a special committee of five senators who would investigate the utility industry's lobbying efforts surrounding the bill. Black's committee was actually one of two such Congressional committees set up for this purpose. When Rep. Owen Brewster (D-Maine) accused Corcoran of threatening to stop construction on the Passamaquoddy Dam in his district unless Brewster voted for the death sentence, the House quickly authorized its Rules Committee, headed by John J. O'Connor (D-New York) to investigate the lobbying tactics of both sides. This was welcome news for the Roosevelt administration, who felt it could still prevail if the public became aware of the manipulative, coercive and unethical lobbying efforts of the utilities. However, FDR placed little faith in O'Connor's committee. O'Connor's brother Basil was the lawyer for Associated Gas & Electric (AG&E), one of the more notorious holding companies. Although no misconduct was ever alleged or proven, the House committee's impartiality was called into question. The President was pinning his hopes squarely on Black's panel. [59]

|

|

Hugo L. Black |

Wheeler deliberately delayed calling the joint conference committee into session in order to give Black sufficient time to develop enough evidence of fraud and misrepresentation to arouse public opinion. When the conference finally convened, Wheeler and Rayburn insisted on the presence of Cohen and Dozier Devane of the Federal Power Commission, both of whom had helped draft large parts of the original bill. Huddleston vehemently objected. He pointed out that the conference committee's deliberations were an executive session. It was to be closed to the public and no one but the conferees could be present. Both Wheeler and Rayburn knew full well that Huddleston was right. However, this ploy gave Black's investigative committee precious time to pursue its probe. [60] Black used this time to full advantage. The morning after his committee was created, Senate investigators entered the Mayflower Hotel offices of chief utility lobbyist Philip Gadsen and promptly brought him to testify before the committee. Armed with subpoenas, the investigators then searched Gadsen's files, both business and personal. Black cornered the head lobbyist into reluctantly admitting that his Committee of Public Utility Executives had already spent over $300,000 to defeat the Wheeler-Rayburn bill. Black further tried to ascertain the real purpose of the high fees paid to various law firms. Gadsen explained that these payments were for advice as to the legal interpretation of the bill, analyses of its provisions, and preparation of various amendments. The following interchange between Gadsden and Black illustrated the thin line between providing legal services and outright lobbying;

BLACK: They did not have anything to do, of course, with trying to defeat the bill?

GADSDEN: Oh, no; not a thing. Their job was to advise us.

BLACK: They were to advise you how to defeat it.

GADSDEN: That is right.

The actual cost of the lobbying effort became a focus of the Black committee throughout the investigation. Counting the amount testified to by Gadsen, the investigation would eventually uncover industry expenditures of over $1.5 million in connection with the fight to defeat the Wheeler-Rayburn bill. This amount was no doubt a minimum — Black later estimated the utilities spent five times that amount in pursuit of their lobbying efforts. This naturally led to another question. What sort of corporate financial structure permitted the expenditure of such astronomical sums? Of particular interest to Black was AG&E, which had no money to pay dividends, yet was able to pay out over $1 million to defeat this legislation. This strange contradiction seemed to suggest the corporate mismanagement of "other people's money." [61]

After grilling Gadsen, Black turned his attention to the forged telegrams which had flooded Congressman Driscoll's office. The testimony of Jack A. Fisher, manager of the Western Union office in Warren, Pennsylvania, shed light on this part of the utilities campaign. Fisher testified,

"During the time the bill was between the House and the Senate, Mr. Herron (an official of Utilities Investing Corporation, which itself was a subsidiary of AG&E) would come in almost daily for a period of an hour... or two ... and he would dictate these messages to me and the signatures, and his signatures were obtained from a list which he had in his hand, or from the city directory."

Fisher stated that he had no reason to challenge Herron's authorization to sign the telegrams because, as an employee of Western Union, his sole interest was in generating revenue for his company.

Fisher also testified that someone in Warren had carefully burned all records of these forgeries despite the existence of a federal law that required copies of all telegrams to be retained for at least one year. He also recalled Herron pointing to the place the records were kept and suggesting "it would be a good idea if somebody threw a barrel of kerosene in the cellar." [62]

The utilities also employed other means to gather signatures. Under questioning from Black, F. R. Veale, general superintendent of the eastern division of Western Union, disclosed that messenger boys, paid three cents for each signature, had collected authorizations for the utility interests. Western Union officials revealed that its central headquarters in New York had informed the local offices of the imminence of the telegraphic deluge several weeks in advance so that they would be ready for the increased business. The utilities took care to cover their tracks well. Their agents paid for the telegrams in cash so no written record would exist.

The utility lobby did not rely solely on the city directory or paid solicitors to gather signatures. They also exerted undue influence on their employees to sign these messages. The Metropolitan Edison Company took the personnel records of its New York Street Railway System and signed the names of every employee and his next of kin, including at least one dead man, to the messages. [63]

Rayburn decided it was time to test the waters in House again. He filed a motion asking the House to instruct its conferees to accept the Senate's death sentence provision. He then played his trump card. That morning, E. P. Cramer, an advertising agency employee, testified that he had initiated the idea of a "whispering campaign" designed to create popular suspicion that the "new dealers and especially the 'New Dealer-in-chief' are either incompetent or insane. . . ." Cramer submitted the idea to C. E. Groesbeck, chairman of the board of directors of EBASCO. According to Groesbeck, the idea never received serious consideration. However, there was evidence that the chairman's assistant responded that the suggestion was "very pertinent." [64]

Rayburn had this read into the record and then awaited the vote on his motion. Much to his surprise and dismay, the motion was soundly defeated by a vote of 209-155. Weeks of sensational testimony before Black's committee had gained only nine votes for the death sentence provision. Rayburn believed that his last hope of getting the administration's bill through the House was quickly slipping away.

While a dejected Rayburn was beginning to lose hope, Black remained confident. He had his sights set firmly on the sprawling AG&E empire. This firm was considered such a black sheep in the industry that it was excluded from joining the Committee of Public Utility Executives lobby. Black was certain that if he could get AG&E president Howard C. Hopson before the Senate committee, he could permanently turn the tide against the utility industry. [65] The only question was whether Black would get that opportunity.

THE HOPSON HUNT

Compelling Hopson to appear before the Black Committee would prove to be a challenge. He had a long and established record of avoiding such appearances. One year earlier, he successfully evaded Ferdinand Pecora's Senate Banking Committee for months on end until a United States marshal finally tracked him down in Chicago. Black instituted a similar nationwide search on July 31st. [66] Despite several promising leads, Hopson evaded the Senate investigators for almost two weeks. Then on August 12th, agents of the House Rules Committee announced they had found the elusive power magnate and that he would appear as a witness before their Committee the following morning. [67] O'Connor's questioning of Hopson during the Rules Committee sessions was so amicable that it drew widespread criticism. As such, it came as no surprise when later testimony showed that Hopson or his attorney had arranged in advance to surrender to O'Connor's committee. In order to secure Hopson's presence, it appears O'Connor agreed to help Hopson avoid appearing before Black's panel.

As expected, Black tried to get Hopson before his own committee during those times when he was not testifying before the House. An agent of the Senate committee finally succeeded in serving a subpoena on Hopson. Hopson's attorney, W. A. Hill, with assistance from O'Connor and the District of Columbia police, had blocked the first attempt. Black's committee called the policemen involved and listened to their version of the facts before taking further action. The evidence indicated a well thought-out plan to prevent Hopson's appearance before the Black Committee. After their subpoena was served, Black called his committee to order and awaited Hopson's and his attorney. When they did not show at the time specified in the subpoena, Black went directly to the floor of the Senate and obtained, by unanimous vote, a contempt citation. This maneuver appears to have gotten Hopson's attention — he voluntarily appeared the next day. O'Connor made one last attempt to shield Hopson from the Senate committee. He introduced a resolution which would have directed the Sergeant-at-Arms of the House to arrest Hopson and keep him in custody until O'Connor finished questioning him. Such action would have effectively blocked Black from ever interrogating Hopson, as it would have nullified the legal effect of the Senate Committee's subpoena. O'Connor's action failed when the members of his own committee refused to support him. O'Connor then agreed to a compromise whereby the two committees divided Hopson in two in a "Solomon like" manner. The compromise provided that the House would question him each morning, the Senate each afternoon. [68]

Hopson quickly proved to be worthy of the pursuit. Once Black had Hopson before the Committee, the full story of the utility lobby's campaign to defeat the Wheeler-Rayburn bill began to emerge. Black elicited more information from Hopson in two hours than O'Connor had in two full days of hearings. Black began by focusing on Hopson's attempt to influence the press' editorial policy by withholding advertising dollars. He quoted from a telegram signed by Hopson, "Am inclined to think we ought to withhold patronage of this paper in line with our former practice... " Hopson testified that he thought it unwise for AG&E to advertise in papers which ignored the worthwhile contributions of the utilities and instead published only anti-utility propaganda. He also confirmed what had been hinted at in the earlier FTC investigation of the utilities. [69] Hopson told of a vast propaganda campaign, which had begun as early as 1919. This effort was accurately described in the FTC study, which concluded that, "measured by quantity, extent, and cost, this was probably the greatest peace-time propaganda campaign ever conducted by private interests in this country."

This campaign was concentrated in two areas — the press and the schools. Hopson confirmed that the industry recognized the importance of these institutions in the formation of public opinion. In the schools the utilities put their message across by employing teachers for the summer, by inviting teachers to help plan courses in utility studies, by making direct money payments to leading universities, and by applying pressure on the textbook publishers. As for the press, Hopson testified that its members yielded easily, especially when induced by large advertising expenditures. The utilities supplemented this influence by purchasing a controlling interest in a number of newspapers. [70]

Black then returned to the letter writing campaign. He found in Hopson's correspondence, as early as February 21, 1935, a suggestion of the plan. Hopson's letter stated that it would be best to write letters requiring replies because "that makes it necessary to do a little work to answer them, and they will appreciate more fully the volume of the opposition." Hopson not only confirmed that he was the architect of the letter writing and telegram scheme, he also admitted to inventing the "widows and orphans" angle to drum up opposition to the Wheeler-Rayburn bill. [71]

As the questioning moved into the area of Hopson's personal finances, and the financial structure of AG&E, he suddenly became an argumentative and reluctant witness. Black, with the backing of his entire committee, reminded Hopson that the contempt proceedings, and a possible jail sentence, were still hanging over his head. This tactic had the desired effect, as Hopson willingly answered the committee's questions on this subject. [72] He testified that AG&E was compromised 164 companies, 104 of which were operating companies. The remaining firms were management companies, engineering companies, or vendors of electrical appliances. Hopson owned the two companies at the top of the AG&E pyramid, through which he controlled an enterprise with annual earnings of $100 million and assets worth over $900 million. [73] He also disclosed that while the AG&E's 350,000 investors had not received a dividend for years, Hopson and his family had been paid over $3 million between 1929 and 1933. He also admitted to spending over $1 million to fight the Wheeler Rayburn bill, all of which had been borrowed from various banks. When pressed on the issue, he confessed that the money to repay this loan would come from the operating companies. As a practical matter, this meant the cost of opposing the bill would be ultimately passed on to the consumer.

On August 22nd, Black concluded his committee's investigation of the holding companies lobbying practices. By all accounts, he had done the near impossible. As sensational disclosure piled upon sensational disclosure, he steadily turned the tide of public opinion against the utilities. In less than two months, the perception of this industry changed entirely. Instead of being viewed as the victim of an overzealous government, it was now seen as greedy, abusive villain deserving of extinction. [74] It was now up to Roosevelt, Wheeler and Rayburn to seize upon this momentum and close the deal.

THE BARKLEY COMPROMISE

Despite the shift in public opinion generated by Black's investigation, the bill was still hopelessly deadlocked in the conference committee. The Senate conferees continued to stand firmly for the death sentence clause. Among the House conferees, Rayburn was still outnumbered by Huddleston and the Republicans. In an adroit political move, Roosevelt decided to seek a compromise that would still eliminate the holding companies while allowing the House members to save face. Administration officials and congressional leaders, minus Wheeler and Rayburn, forged a new section 11. This new version kept the essence of the original death sentence provision, while avoiding some of its harsher language. The President needed someone who was respected by both parties to present the new bill to the joint conference committee. He assigned this task to Senator Alben W. Barkley (D-Kentucky), who would later become Vice-President in the Truman Administration. As such, this proposal was referred to as "The Barkley Compromise. [75]

Under the revised bill, a holding company was defined as any investment device that controlled 10 percent or more of an operating company's stock. The holding companies would be allowed to have two levels, a holding company on top and one or more operating subsidiaries below. The new bill contained an exception not found in the original version:

|

|

Sen. Alben Barkley (D-Kentucky) |

"The Commission shall permit a holding company to control one or more additional integrated systems located in a single state or adjoining states on an affirmative finding that such additional systems cannot be operated independently without loss of substantial economies and that localized management, efficient operation, and effective regulation will not be impaired thereby." [76]

The bill also gave the SEC some latitude that was not found in the original version -it gave the Commission the discretion to permit the indefinite continuance of any company who was not in compliance with the Act. In all other respects, it remained unchanged.

Wheeler and Rayburn readily accepted the changes. However, Huddleston and the other House conferees persisted in their steadfast refusal. This left Rayburn with one risky alternative — file another motion asking the House to instruct its conferees to accept the compromise. Rayburn approached this move with much trepidation. After all, he had pursued the same action only three weeks and had been soundly defeated. However, in the final analysis Rayburn was left with no choice. On August 22nd he filed the motion, which was promptly set for a vote the next day. Hopson's testimony, the forged telegrams and the other disclosures which came from Black's investigation were enough to convince the House to reverse itself. By a vote of 219-142, the members instructed their conferees to accept the compromise.

On August 24th, exactly two hundred days after it was introducted by Wheeler and Rayburn, the full bill, complete with the compromised death sentence, passed both the House and the Senate. [77] At a White House ceremony on August 26, 1935, President Roosevelt officially ended what had become a contentious and draining legislative war. While Wheeler, Rayburn, Cohen, Corcoran and others stood behind him, he signed the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 into law.

COURT CHALLENGES AND POST-PASSAGE COMPLIANCE

Following passage of the Act, the vast majority of the public utility holding companies refused to register with the SEC, as was now required. The SEC, which could have denied the non-registering companies use of the U.S. mail and other instruments of interstate commerce, agreed to hold the Act in abeyance while it brought a case against EBASCO, to test the constitutionality of the new law. As part of its legal strategy, the SEC sought to limit the test to the registration feature only. The Commission wanted to first establish its right to regulate the holding companies before testing the validity of the death sentence provision. The reasoning was that even if the death sentence was eventually thrown out, the Commission would still have a court tested framework from which to fashion a new law. EBASCO, on the other hand, sought a ruling on the entire Act. [78] EBASCO lost twice in the lower courts and then placed the issue before the Supreme Court. On April 1, 1938, the court entered a 6-1 decision upholding the registration provision. The court also declined to rule the Act as whole, therefore leaving the rest of the law open to future adjudication. In an ironic twist, newly appointed Justice Hugo Black joined in the majority opinion. [79]

This was a sweeping victory for the government. SEC Chairman William Douglas could now carefully choose the first holding company to "simplify" under the death penalty clause. Douglas chose wisely, initially targeting Utilities Power & Light (UP&L), which was already in receivership, despite having assets worth over $300 million. UP&L was controlled by the Atlas Corporation, a large investment trust. After reviewing the SEC's proposed plan, Atlas' president, Floyd Odium stated that he would not appeal any "death sentence" for UP&L. He also added that the Commission's proposal was "good economics apart from any statutory requirement. . . ." Chairman Douglas had effectively sent a message to the holding companies. While disclaiming any further death sentence plans, "because of our belief that the substantial companies in the industry are making progress" in designing such reorganizations, Douglas also declared, "This action on the part of the commission means the commission means business."

Douglas had reason to be cautiously optimistic about the holding companies willingness to comply with the Act. While the entire industry vowed to fight the law immediately after its enactment, 44% of the nation's holding companies had already registered with the SEC before the Supreme Court handed down its ruling in the EBASCO case. In fact, one of the largest such firms, American Water Works and Electric Company, became the first to voluntarily submit a reorganization plan on August 25, 1937. [80]

It was, however, inevitable that the constitutionality of the death sentence provision would eventually be adjudicated. In 1942, the SEC issued an order requiring the North American Company to divest itself of all its properties, except those in the St. Louis area. The company refused to do so without a court battle. The case was argued before the Supreme Court in November of 1945 and a decision was rendered on April 1, 1946. The Court let the ax fall on the holding companies by upholding the death sentence clause. No one was surprised by the 6-0 opinion. Speaking for the majority, Justice Frank Murphy wrote, "Congress, in passing the act, was concerned with the economic evils resulting from uncoordinated and unintegrated public utility holding company systems. These evils were found to be polluting the channels of interstate commerce. . . . The national welfare was thereby harmed. . . . Congress therefore had power to remove those evils." [81]

More than a decade after President Roosevelt first signed it into law, the Wheeler-Rayburn Act had been validated in its entirety. Throughout the rest of the 20th century, it would serve to minimize the abuses of the holding company device in the public utility field, insuring that protection and benefit flowed to the operating companies, utility investors, utility consumers and public generally.

CONCLUSION

The Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935 was the result of what many American historians call "the fiercest congressional battle in history." While this assertion is a matter of opinion and open to interpretation, it is a fact that this piece of New Deal legislation presents an interesting case study in human behavior. The public utility holding companies, and the men who controlled them, paint a classic picture of greed and manipulation, and prove that Lord Acton was correct when he stated, "power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely." On the other end of the spectrum, Sam Rayburn, Burton K. Wheeler and Hugo Black overcame one of the most powerful political lobbies ever assembled. Their efforts in this regard are text book examples of tenacity, courage and perseverance.

The utility holding companies began enriching themselves at the expense of the average consumer as early as the 1890's. In addition to milking profits from the operating companies, this device allowed a concentration of economic power to be held by a select few. Therefore, when the Roosevelt administration introduced a bill that would totally eradicate these firms, they launched a no holds barred campaign in opposition. This is a bill that became law against all odds. With an inexhaustible supply of money, and a propaganda campaign that captured and won over the American public, the utilities almost succeeded in killing the bill on several occasions. However, the parliamentary and political skills of both Wheeler and Rayburn kept it alive long enough for the investigative talents of Black to shed light on the true nature of the holding companies.

Although the final bill did not entirely abolish these companies, as FDR originally intended, the finished product was actually something much better — a law that proved to be extraordinarily effective in ending the abuses of the holding company, while at the same time preserving the existing benefits of the holding company system. The Act accomplished this objective for over seventy years. Unfortunately, the history of this Act does not have a happy ending. At the beginning of the 21st century, the utility industry, and would-be owners of utilities, began to lobby Congress to repeal the Wheeler-Rayburn Act on the grounds that it was outdated. On August 8, 2005, the Energy Policy Act of 2005 passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law. Thus, the Wheeler-Rayburn Act was repealed, despite objections from consumer groups, environmental organizations, union and credit rating agencies. [82] It was replaced with a much weaker set of laws known as the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 2005. Gone are most of the safeguards which prevented a concentration of economic power by a small group of wealthy investors. Modern-day Morgans and Insulls can now invest in public utility holding companies with little or no restrictions.

It remains to be seen if history will repeat itself.

[1] William E. Mosher and Finla G. Crawford, Public Utility Regulation, (New York, Harper and Brothers, 1933) 322

[2] Department of Energy, "Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935:1935-1992", available from http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/ftproot/electricity/0563.pdf, Internet, accessed March 28, 2010.

[5] Neal Baldwin, Edison: Inventing the Century (New York, Hyperion, 1995) 3—5

[6] Mosher and Crawford 324

[7] William H. Anderson, "Public Utility Holding Companies: The Death Sentence and the Future", The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, Vol. 23, No. 3 (University of Wisconsin Press, 1947) 244-254

[11] Richard Freeman and Marsha Freeman, "Regulation: The Fight Which Saved the Nation", American Almanac, (February, 2001) 45-47

[16] Time Magazine, Power: Death of an Era (July 25, 1938)

[18] G. Lloyd Wilson, James M. Herring, and Roland B. Eutsler, Public Utility Regulation (New York, McGraw Hill, 1938) 266--267.

[19] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Statement Concerning Proposals to Amend or Repeal the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, June 2, 1982, 6- - 12

[21] Summary Report of the Federal Trade Commission on Utility Corporations, Senate Document 92, 70th Congress, 1st Session, 840--841

[22] Department of Energy Report, 12

[23] FTC Report on Utility Corporations, Part 72a, 298-299

[24] Wilson, Herring, and Eutsler, 268

[25] FTC Report on Utility Corporations, 466—467

[26] Freeman and Freeman, 4

[27] Time Magazine, Power: Death of an Era (July 25, 1938)

[28] Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Age of Roosevelt: The Politics of Upheaval, Vol. 3 (New York; Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958), 302

[30] Report of the National Power Policy Committee on Public Utility Holding Companies, House Document No. 137, 74th Cong., 1st Sess. (March 12, 1935) 4-8

[33] D.B. Hardeman and Donald C. Bacon, Rayburn: A Biography, (Austin: Texas Monthly Press, 1987) 169

[36] Congressional Record , Jan. 4, 1935,374-378

[37] Hardeman and Bacon, 171

[40] Time Magazine: Propaganda vs. Propaganda (Mar. 25 1935)

[46] Joseph Barnes, Wilkie, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1952) 82-83

[47] Hardeman and Bacon, 175

[50] Time Magazine: Propaganda vs. Propaganda (Mar. 25 1935)

[51] Hardeman and Bacon, 175

[53] Time Magazine: Lobby vs. Lobby (Jul. 8 1935)

[54] Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Press Conference #216, June 28, 1935

[55] Schlesinger, 315-316

[56] Time Magazine: Lobby vs. Lobby (Jul. 8 1935)

[57] New York Times, June 30, 1935

[58] St. Louis Post Dispatch, July 3, 1935

[59] Time Magazine: Hopson Hunt (Aug.19 1935)

[60] Schlesinger, 323-324

[61] Senate Special Committee to Investigate Lobbying Activities, Investigation of Lobbying Activities: Hearings, 74 Cong., 1 Sess. (1935) 611-650

[65] Hardeman and Bacon, 193

[66] New York Times, August 1, 1935

[67] New York Times, August 13, 1935

[68] Hardeman and Bacon, 195

[69] New York Times, August 19, 1935

[70] William A. Gregory and Rennard Strickland, "Hugo Black's Congressional Investigation of Lobbying and the Public Utility Holding Company Act: A Historical View of the Power Trust, New Deal Politics and Regulatory Propaganda", Oklahoma Law Review, Vol. 29, No. 3 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1975) 548-555

[71] Senate Special Committee to Investigate Lobbying Activities, Investigation of Lobbying Activities: Hearings, 74 Cong., 1 Sess. (1935) 971-992

[72] Hardeman and Bacon, 195-196

[73] Time Magazine: Hopson Hunt (Aug.19 1935)

[74] Schlesinger, 319-320

[75] Hardeman and Bacon, 196-197

[76] Congressional Record, August 22, 1935, 14162-14171

[77] New York Times, August 24, 1935

[78] Time Magazine: War and Reward (Dec.9 1935)

[79] Time Magazine: 6-to-1 (Apr.4 1938)

[81] Time Magazine: The ax (Apr. 8 1946)

[82] Department of Energy, "Recommendations of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission on Technical and Conforming Amendments to Federal Law Necessary to Carry Out the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 2005 and Related Amendments", available from http://elibrary.ferc.gov/idmws/common/opennat.asp?fileID=10900380, Internet, accessed April 1, 2010

Bibliography

Books and Dissertations

Baldwin, Neal. Edison: Inventing the Century. New York: Hyperion, 1995.

Barnes, Joseph. Wilkie, New York: Simon and Schuster, 1952.

Hardeman, D.B. Bacon Donald C. Rayburn: A Biography. Austin: Texas Monthly Press, 1987.

Mosher, William E. and Crawford Finla G. Public Utility Regulation. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1933.

Schlesinger, Arthur M. Jr. The Age of Roosevelt: The Politics of Upheaval, Vol. 3.New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1958.

Wilson, J G. Lloyd, Herring, James M. Eutsler, Roland B. Public Utility Regulation (New York: McGraw Hill, 1938.

Periodicals and Journals

Anderson, William H. "Public Utility Holding Companies: The Death Sentence and the Future". The Journal of Land & Public Utility Economics, Vol. 23, No. 3. (University of Wisconsin Press, 1947).

Freeman, Richard and Freeman, Marsha. "Regulation: The Fight Which Saved the Nation", American Almanac. February, 2001.

Gregory, William A. and Strickland, Rennard. "Hugo Black's Congressional Investigation of Lobbying and the Public Utility Holding Company Act: A Historical View of the Power Trust, New Deal Politics and Regulatory Propaganda." Oklahoma Law Review, Vol. 29, No. 3 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1975).

"Propaganda vs. Propaganda," Time, March 25, 1935.

"Lobby vs. Lobby," Time, July 8, 1935.

"Hopson Hunt," Time, August 19, 1935.

"War and Reward," Time, December 9, 1935.

"6-to-1," Time, April 4, 1938.

"Power: Death of an Era," Time, July 25, 1938.

"The Ax," Time, April 8, 1946.

Newspapers

New York Times 1935, 1937, 1939, 1940,1946.

St. Louis Dispatch 1935.

Government Records and Reports

Energy Information Administration, Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935:1935- 1992. U.S. Department of Energy, 1993.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Press Conference #216, June 28, 1935.

Report of the National Power Policy Committee on Public Utility Holding Companies, House Document No. 137, 74th Cong., 1st Sess. (March 12, 1935).

Senate Special Committee to Investigate Lobbying Activities, Investigation of Lobbying Activities: Hearings, 74 Cong., 1 Sess. (1935).

Summary Report of the Federal Trade Commission on Utility Corporations, Senate Document 92, 70th Congress, 1st Session.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Statement Concerning Proposals to Amend or Repeal the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, June 2, 1982.

Internet

http://elibrary.ferc.gov/idmws/common/opennat.asp?fileID=10900380:

"Recommendations of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission on Technical and Conforming Amendments to Federal Law Necessary to Carry Out the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 2005 and Related Amendments"

|